British artist Mark Leckey — creator of famed club culture docu-hallucination, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999), winner of the 2008 Turner Prize, and longtime NTS Radio host — discusses the terms of art-making in our technological present and our increasingly medieval relationship to representation. His show “3 Songs from the Liver” was on view at Gladstone Gallery, NY, Nov 2024 - Feb 2025.

“AI outputs are not “images” as we know them. And if we try to understand them in that way, then we’re really…. f*cked, you know?”

Following this conversation, keep listening for “Enter Through Medieval Wounds” a radio play by Mark Leckey, which first appeared in essay form in Heavy Traffic 5 (Fall 2024).

For more: markleckey.com & NTS

Experimenting with sharing a text version of the episode’s intro below. If you find this useful, let us know and we’ll do it more often in the future.

-

Intro transcript (Caroline Busta):

On this episode of NM Greenroom we speak with the artist Mark Leckey. This winter, his show “3 Songs From the Liver” was on view at Gladstone Gallery in New York. Many listeners will be familiar with Mark’s work — his 1999 video piece, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is regarded as an essential, highly accurate depiction of the rise of British dance and club culture. And yet what the viewer encounters is not a 1-to-1 portrayal of subcultural activity but rather a hallucination of thereof. To create the work, Mark aggregated and transcoded archival footage from the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, and then extensively edited both the audio and moving image elements. There is no meta voice-over and no didactic “facts” but the piece manages to communicate more about its subject matter in its brief 15 minute runtime, than language likely could have achieved.

We recorded this episode in mid-December 2024, which is to say a few weeks before an ex-green beret self-immolated in a Tesla parked in front of a Trump hotel in Las Vegas and before fires ravaged some 40,000 acres in and around Los Angeles; it was also before the death of David Lynch; and before the inauguration of Donald Trump and JD Vance, who with the help of Elon would immediately slash-and-burn large swathes of the US government and its foreign relations.

This conversation, perhaps mercifully, does not address “current events.” But it does speak to a change in perspective — and a change in our relationship to images that is probably helpful for weathering 2025 and beyond. Most people who grew up in the West learned to see images according to the idea that a picture has something to tell you, and that relationship is linear, the picture transmits information to you, and the utility of that message depends on how well you observe it.

But what if one understood pictures to be inherently interactive, as people in the middle ages commonly did? Image as interface rather than image as view-only screen. Would it make it easier to accept that, in a time of infinite images and machine learning, all images now are archetypal, and none is novel, and that’s ok? Would this understanding help us to let go of the longstanding expectation of originality in image-making. After all, in the model there is no “new”—only proximity (near or far) to this or that archetype or embedding. By letting go of trying to make something unique (which is futile — there are currently some 16000 videos being uploaded to TikTok every minute and, anyway, all images, at least theoretically, already exist in the latent potential of the model) we might feel more able to make something that allows us to uniquely or at least more effectively mediate reality.

For the past year or two with New Models, we’ve been harping on this idea that the creative act no longer happens at the level of “content” but rather up- and downstream of it. Upstream, there is the creating of protocols for how content is produced and engaged. Downstream, there is the metabolizing of that content— whether in the form of commentary or fanfic or memes or any other engagement that, while diluting the high-resolution of the original post, enriches its memetic density. (See: Mark Leckey’s 2009 performance-lecture In the Long Tail, channeling researcher Chris Anderson’s theory thereof.)

In this sense — that the novelty of the image is beside the point (because nothing is novel now) and that creative agency is now located either up and downstream of the image — there is already something medieval to the way we see in 2025. No matter how seemingly unprecedented the image – a roided-out Wednesday frog in a wizard hat, Elon on stage with a chainsaw, a cryptotrader killing himself while livestreaming – this content is ultimately most valuable to us for its archetypal resonance and only insofar as we can mediate our experience of the world through it. And when we do, we literally charge it with attention: liking it, iterating it, recontextualizing it, and otherwise imbuing it with energy that keeps it in circulation. I’m probably stretching the art history here, but Byzantine and medieval icon paintings were also used to mediate one’s experience of the world: the faithful would physically interact with them, praying before them, touching them, charging them with their own life-force, and then carrying miniature renderings of the same icons and scenes, sharing them with others as they travelled. If this theory holds, perhaps we could see their role — like that of 1000 year old icons — as less to transmit new information than to be an interface. After all, both the ‘virgin and child’ motif and a virgin/chad meme are devices for focusing collective attention and thereby synchronizing consciousness.

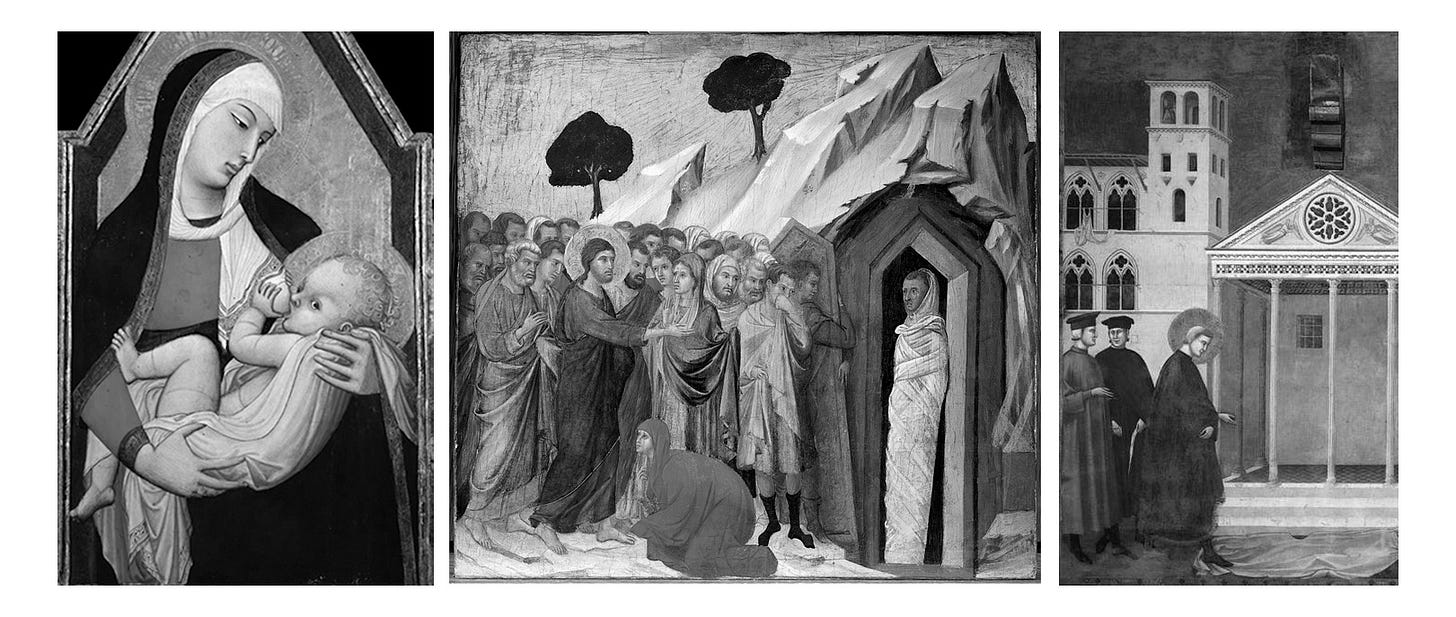

At the entrance to Mark’s Gladstone show was a reproduction of Pere Borrell del Caso’s famous (dare I say memetic) 1874 trompe-l’oeil painting of a boy climbing out of the painting’s frame (although in Mark’s version, the boys’ eyes are shielded by iridescent glasses). Within the gallery, much of the show was either narrowly spotlit or self-illuminated, each component seemingly alive as if by rays pouring in through a cathedral’s clerestory windows. Serendipitously, a spectacular exhibition of late gothic painting was on view concurrently uptown at the Met. Titled “Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300 - 1350,” it reunited more than 100 works from this one-time metropolis sited along major trade routes of the time. Via Duccio, the Lorenzetti brothers, and Simone Martini, among others, one could be immersed in an era of art-making when European artists were aware of but not yet fully sold on the trend toward making images spatially naturalistic (as were Giotto and his workshop 50 kilometers to the south in Florence).

For Sienese painters, the portrayal of icons and canonical motifs leaned in to human relatability, with work that was emotional, personal, and psychologically intimate – the christ-child greedily nursing while making eye contact with the viewer; the onlookers skeptically watching Lazarus’s decomposing body being revived by Jesus while those closest to the tomb recoil at the stench. And yet the space in which these scenes appear remains “artificial,” even disorienting. A viewer cannot enter the image, it is too flat, too crowded, too covered in blinding gold. Instead, one needs the help of the saints, one needs to commune with them, to be displaced from one’s individual body by them … in a way, to merge with them, in order to operate on their realm (beyond the reach of Earth-bound physics). To again stretch the art historical interpretation, but could there be an analogy here to today’s cloud or large language model being a space beyond mortal human agency and maybe even the petitioning of, god help me, algorithms to meaningfully intervene on that realm?

Mark speaks of this more Byzantine treatment of representational space in his NM Greenroom conversation. And it is the kind of space that he created in his show at Gladstone. Talking about one of the central works, a video installation called Mercy I Cry City (2024), he describes it as depicting “a city that existed before the invention of single-point perspective and will be built after that perspective has exhausted itself.”

And indeed the further into this nonlinear post-neural-media weirdening we travel, the less sense any kind of one-point perspective seems to make. In fact, relinquishing ingrained expectations of a singular vanishing point may be centrally important to effective expression in the years to come—whether that’s letting go of the assumption of creative genius as something belonging to an individual (rather than emergent from a collective scene), or expecting the kind of unifying top-down mass narratives that institutions used to provide, or an understanding of the world as organized by Western hegemony, when by all accounts global power is now multipolar.

Earlier this year, Dean Kissick texted with the phrase, “Reality is a collective hallucination,” and it’s been haunting (or maybe deeply motivating) me ever since. As, if reality is indeed a collective hallucination, an understanding of whatever mediates the coexisting collectives and their competing realities is of utmost importance.

There is much more to say here, but let’s get to the conversation [NM Greenroom: Mark Leckey] …